Four Tips for Getting Knowledge Out of SME’s Heads

If you are an instructional designer, it is guaranteed that you will work with a Subject Matter Expert (SME) in order to get your work done. Here are 4 tips for ensuring the relationship (and your work output) is productive.

More often than not, instructional designers create learning on topics that they are not experts in. This means they must rely on subject matter experts (SMEs) to provide the content, while they design the learning process. Trouble is, SMEs are not that easy to work with. It’s likely they have never had to fill this role before and don’t know why you are asking so many questions. Some of them can feel threatened and be purposefully uncooperative. Only twice in my career have I had SMEs say “Hallelujah! You’re here!”

Over my 25-year career designing custom training curriculum for all sorts of industries and topics, I’ve developed a few techniques for getting information out of SME’s heads. See if these work for you.

1 - Do Your Homework

I once had an SME at an aerospace company make me read an entire textbook on Material Requirements Planning (#MRP)– “then you can talk to me,” he said. Let me tell you, if you are not an engineer, that is not fun reading. This SME taught me a very valuable lesson: don’t walk into your meeting expecting them to take you from the ground up. Learn all you can about the topic (and in today’s day and age, that is not hard to do) so that you can at least follow acronyms and ask semi-intelligent questions. And speaking of questions…

2 - Ask At Least Three Questions

Lots of SME’s like to tell you “special case” scenarios to demonstrate their extreme knowledge, but that information doesn’t help someone learning a new skill. No matter what the SME tells you, ask at least three questions to pull out more information or have them explain it in a different way.

Some suggestions are: Is that true in all cases? When would someone do this (what is the trigger)? Why? How did you get from A to B? Is that a typical cause (or outcome)? Can you explain that in a different way? So, is that similar to (relate to a “real world” scenario)?

Example: When working with a casual clothing retailer I was assigned a “shoe guru” who was helping me to design training for the salespeople on the floor (interesting factoid: Nike will not let you sell their shoes of $100 or more if you do not have a full-service footwear sales staff). He was adamant that we had to include the history of each of the 8 manufacturers they represented. Why? Because he was a guru. He loved athletic footwear. But knowing the history of each company was not going to help the salespeople do their jobs better. It was quite a tussle between the two of us,

He: Must be included

Me: People can sell shoes without knowing this

Finally, we compromised and included the eight manufacturers’ histories in an appendix of the “selling shoes bible” we created.

3 - Make Best Guesses For Them To Correct

Most SMEs are so smart and skilled that they don’t know what they know. I remember when I was learning to ride a motorcycle I thought, “This training is terrible, I’d change this, this, and this.” I had every intention of writing to the state entity that ran the school and telling them what they were doing wrong. Now, 15 years in, I have no recollection of why it was so hard to learn.

At times, when I’ve had trouble getting intel out of an SME’s head, I’ve simply gone ahead and made stuff up. Based on observation or best guesses, I’ll document what I think is happening. I have found it is easier for an SME to see what is wrong and correct it, than to tell me out of the gate what is the right way to do something. This is where being an uninformed neophyte is helpful. Sometimes we shouldn’t be getting our direction from the most skilled individual but rather from the newbie.

4 - Give Them Deadlines, Then Move On!

As an instructional designer, you have deadlines to meet (usually impossibly short deadlines, but that’s a different blog post). When you are dependent on an SME for the content (not the learning process, but the content) it can be difficult to stay on track because your deadlines are not the SMEs deadlines. It may seem punitive, but you must give the SME deadlines for reviewing the learning and giving you feedback and if you don’t get it – move on. I generally allow 4 – 10 working days. I have also found it helpful to set a meeting and actually be there in the room (or the Zoom) during the review.

This is helpful in two ways:

If it is an appointment on their calendar, it (almost always) ensures they do the review

It can save me time by doing the edits during the meeting

The longest meeting of my life was a 6-hour review and working session, via phone, but we got it done!

Bonus Tip: Thank Them Profusely!

You couldn’t have gotten your job done without the help of the SME, so be sure to thank them profusely. Put a recommendation on their LinkedIn profile. Drop an email to their boss thanking them for allowing the SME to take the time to work with you and praising how easy they were to work with. You may even go so far as sending a small gift – once, a colleague and I so enjoyed working with an SME for the better part of a year that we had our picture taken with him and framed it to leave behind as a memento.

That Word Doesn’t Mean What You Think It Means

Too frequently, workplace training departments think they are offering a “blended learning experience” by offering the same class in different iterations, so that people can take the class in the format that best meets their needs. That is NOT what blended learning is.

This is a short post with a big impact.

After spending two weeks scoring Chief Learning Officer Learning Elite submissions it's imperative that I inform you that the word blended does not mean what you think it means.

It's not just the Learning Elite submissions either, I have run into this confusion many times when talking to training and development professionals. For some reason, T&D professionals believe that if you offer a course in the classroom, and via e-learning, and via a virtual platform (or various other delivery methodologies) you are offering “blended learning.”

WRONG

What you have is a menu.

Here is an easy way to remember what blended is vs. what a menu of options is: Do you like your potatoes baked, mashed, or French-fried? All three are potatoes. You could eat all three “potato delivery methods” at the same meal, but you’d still be consuming the same fundamental thing.

The same holds true for training courses. Three different iterations of the same class are still one course.

What a blended course looks like is offering different portions of one course in different formats which are utilized to best achieve maximum learning.

For instance, if you were teaching how to use graphic design software, you might have the learners first review a glossary of terms such as font, pixel, saturation, etc. You would not need to waste valuable classroom time teaching them terms and their definition. They could have a handy resource to do so prior to coming to the class, as well as to use throughout the class as a reference tool. The next portion of the blend would be to have students come together in the classroom, to use the software hands-on. The next portion of the blend might be to give each learner an assignment to complete, asynchronously (on their own time, not with others) over the next two days and to bring it back for review and critique. During those two days, you might offer “office hours” so that learners could contact you with any challenges they were experiencing during the independent assignment.

That is a blended learning experience. It utilizes four different training methodologies which, in total, create the entire course.

Independent study (reviewing terminology)

Classroom

Independent activity (practice over two days)

1:1 coaching

You don't need to take valuable classroom time teaching people terminology nor do you need to keep the group together for them to complete an independent assignment. So a blended course is divided into chunks, each of which uses a different teaching or learning methodology, to best achieve the learning outcome.

Which takes longer to teach – how to launch a missile or how to sell insurance?

We often work with 2 and 3 clients simultaneously. It helps with productivity because sometimes you just hit a wall in your thinking when focused on one industry or topic and switching to another helps to get your creative juices flowing again.

One year we were working with both the US Navy and a large insurance company that sold disability insurance through employers (if you were an employee, you could elect to add this disability insurance through your employer).

The Navy project involved radar, sonar and firemen on a nuclear sub, working together to determine when it was appropriate to launch a missile – all three roles must work in unison.

The insurance company project involved training new-hires, right out of college, to sell their employer’s policies to companies.

The Navy required 6 weeks of training.

The insurance company required 40 weeks of training.

It is a dichotomy that has stuck with us for decades. It only takes 6 weeks to learn to launch a missile, but 40 weeks to learn to sell insurance?

Some of the explanatory factors may include:

Launching a missile is based on very matter of fact yes/no decisions.

Insurance sales is based on personal interactions – can you get past the gatekeeper? Do you have something viable to offer? Can you answer questions that will not be the same from prospect to prospect?

To teach sales you must teach a lot of variables and how those variables might present themselves. Every interaction will be different.

To launch a missile the people who execute are not the people who make the decision to execute – once they get the order, they combine their data and within very narrow parameters, choose the best opportunity to launch.

Take away – when determining the design of your training or how long it will take to learn – consider how many variables will be in play and how many you can account for in a learning environment.

Here's How You Can Create Training Without Knowing a Thing About the Topic

Have you ever had to design a training program for a topic you just didn't get? Us too!

The wonderful thing about being a professional instructional designer is that you don't actually have to understand the topic, but you MUST understand the process of how people learn.

If you understand how to design learning - the topic is irrelevant.

For instance, we created Row, Row, Row Your Family Feud Boat (download, here) when we were charged with helping financial planners to overcome client objections to moving to a new platform.

At first, we referred to it as a "product" and we were quickly corrected: It's not a product, it's a platform.

When then changed our wording to "service." Wrong again. It's not a service, it's a platform. How could we design training to overcome objections to a platform if we didn't even get what that WAS?

Easy - you design a learning process and have the learners themselves fill in the content.

Check it out here. You can use this design for all sorts of topics.

Better Learning Through Interleaving

Interleaving is a largely unheard of technique – outside of neuroscience - which will catapult your learning and training outcomes. The technique has been studied since the late 1990’s but not outside of academia. Still, learning and incorporating the technique will make your training offerings more effective and your learners more productive.

What is it?

Interleaving is a way of learning and studying. Most learning is done in “blocks” – a period of time in which one subject is learned or practiced. Think of high school where each class is roughly an hour and focuses on only one topic (math, history, english, etc.). The typical training catalog is arranged this way, as well. Your organization might offer Negotiation Skills for 4 hours or Beginner Excel for two days. The offering is focused on one specific skill for an intense period of time.

Interleaving, on the other hand, mixes several inter-related skills or topics together. So, rather than learning negotiation skills as a stand-alone topic, those skills would be interleaved with other related topics such as competitive intelligence, writing proposals or understanding profit-margins. One of the keys of interleaving is that the learner is able to see how concepts are related as well as how they differ. This adds to the learner’s ability to conceptualize and think critically, rather than simply relying on rote or working memory.

How Does it Benefit?

Interleaving is hard work. When utilizing interleaving, the brain must constantly assess new information and form a “strategy” for dealing with it. For example, what do I know about my competitor’s offering (competitive intelligence), and how am I able to match or overcome that (negotiation skills)? While the technique is still being studied, it is suspected that it works well in preparing adult learners in the workplace because “work” never comes in a linear, logical or block form. You might change tasks and topics three times in an hour; those tasks may be related or not –the worker needs to be able to discriminate and make correct choices based on how the situation is presented.

Interleaving helps to train the brain to continually focus on searching for different responses, decisions, or actions. While the learning process is more gradual and difficult at first (because there are many different and varied exposures to the content), the increased effort results in longer lasting outcomes.

What’s interesting is that in the short term, it appears that blocking works better. If people study one topic consistently (as one might study for a final exam), they generally do better – in the short term - on a test than those who learned through interleaving.

Again, the only studies that have been done have taken place in academia, but here is an example of the long-term beneficial outcomes of interleaving. In a three-month study (2014) 7th-grade mathematics students learned slope and graph problems were either taught via a blocking strategy or an interleaving strategy. When a test on the topic was conducted immediately following the training, the blocking learners had higher scores. However, one day later, the interleaving students had 25% better scores than the blocking learners and one month later the interleaving students had 76% better scores! Because interleaving doesn’t allow the learner to hold anything in working memory, but instead requires him to constantly retrieve the appropriate approach or response, there is more ability to arrive at a well-reasoned answer and a better test of truly having learned.

How Can You Use Interleaving?

As mentioned earlier, although concentrating on one topic at a time to learn it (blocking) seems effective, it really isn’t because long term understanding and retention suffers. Therefore one must question whether there was actual learning or simply memorization. If your goal is to help your trainees learn, you’ll want to use an interleaving process. Warning: Most companies won’t want to do this because it is a longer and more difficult learning process and the rewards are seen later, as well.

Make Links

The design and development of your curriculum(s) doesn’t need to change at all – simply the process. First, look for links between topics and ideas and then have your learners switch between the topics and ideas during the learning process. For instance, our Teaching Thinking Curriculum does this by linking topics such as Risk, Finance, and Decision Making. While each of those is a distinct topic, there are many areas of overlap. In fact, one doesn’t really make a business decision without considering the risk and the cost or cost/benefit, correct? So why would you teach those topics independent of one another?

Use with Other Learning Strategies

Interleaving isn’t the “miracle” approach to enhanced learning. Terrific outcomes are also achieved through spaced learning, repeated retrieval, practice testing and more. Especially when it comes to critical thinking tasks, judgement requires multiple exposures to problems and situations. Be sure to integrate different types of learning processes in order to maximize the benefit of interleaving.

Integrate Concepts with Real Work

Today’s jobs require people to work on complex tasks with often esoteric outcomes. It’s hard to apply new learning to one’s work when the two occur in separate spheres and the real-world application isn’t immediate. Try to integrate topics to be learned with the work the learner is doing right now. For example, for a course in reading financial reports (cash flow, profit/loss, etc.), rather than simply teaching the concepts with generic examples of the formats, the learners were tasked with bringing the annual report from two of their clients (learners were salespeople). As each type of financial report was taught, the learners looked to real-world examples (that meant something to them) of how to read and interpret those reports.

Ask the Learners to Process

Too often we conclude a training class by reviewing what was covered in the class. Rather than telling the learners what just happened, have them process the concepts themselves. This is easiest to do through a writing activity. You might ask the learners to pause periodically, note what they have learned, link it to something they learned earlier, and align it with their work responsibilities. For instance: I will use my understanding of profit margins and financial risk to thoughtfully reply to a customer’s request for a discount or to confidently walk away from the deal. It’s not about the sale, it’s about the bottom line. The process of writing helps the learner to really think through the concepts just taught and it allows them to go back over their learning in the future to remind themselves of the links they made within the curriculum and between the curriculum and work responsibilities. Interleaving enables your training to be more effective and your learners to be more accomplished and productive.

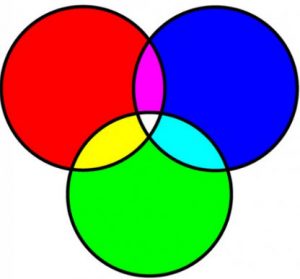

Now You See It... Now You GET It - The Power of Visuals in Learning

First, some important factoids regarding our vision:

Vision is the hardest working process in our bodies

Vision takes up 30% of the brain's processing capabilities

Neuroscientists know more about our vison than any other sensory system in our body

We don't see with our eyes, we see with our brains

As important as vision is for survival (is that a saber toothed tiger I see charging toward me?) it also trumps all our other senses when it comes to learning, interpreting and understanding the world around us. Vision is probably the best single tool we have for learning anything, so says John Medina author of Brain Rules (check it out at www.brainrules.net).

One of the reasons that vision (and thereby the use of visuals) is so powerful is because something that we see is easy to label, identify, categorize and recall later. What's the circular thing with buckets that twirls at the carnival? Oh right. A Ferris Wheel.

Visual input is so important, neuroscience has given it a fancy title: Pictorial Superiority Effect (or PSE). In one experiment, test subjects were shown 2,500 pictures for 10 seconds each. Several days after the exposure to the pictures, the subjects were able to recall 90% of the pictures. The same type of experiment, utilizing words, fell to an abysmal 10% recall three-days after exposure. But the RIGHT words can help learners create visuals.

Words Create Pictures

The very tall man folded his body, in order to fit in to the sports car, then sped away.Did you "see" those words in your mind as you read them? Everyone did. And everyone saw a different picture. Very tall is relative. Sports car is generic. But you have a picture in your head related to what you just read. We don't see with our eyes - we see with our brains. You did not physically see the scenario that was described but you have a picture of it in your mind. Amazing.

Pictures Create Emotion

Additionally, pictures can evoke emotion, which helps with retention and recall. Think about the image of the Ferris Wheel a few paragraphs back. You pictured a Ferris Wheel in order to help you recall it's name, didn't you? Many of you also remembered experiencing a Ferris Wheel in some way - either the glee (or terror) of riding it, looking up at it all colorful and bright, or being at the carnival - with the smells and sounds - where you encountered it. You have a vivid memory of a Ferris Wheel. That memory is defined in a picture.

Important Ways to Incorporate Visuals in Learning

Because using visuals is so crucial to understanding and remembering, it is imperative that we give just as much thought to the visuals we use in training, as to the content we are creating. Here are some ways you can utilize visuals in your training:

Slides / Photos - include pictures - especially photos - especially photos of people - on your slides. Photos are more realistic than graphics or clip art and therefore more engaging to the brain. Photos of people are especially memorable. We like to see people "just like us."

Physical objects - whenever possible, include a real representation of the visual. Sometimes you'll have to stretch to make it work - but the stretch will be worth it because it will sear the message in to the learner's brain. More than 2 decades ago I attended a presentation given by a man. I have no idea who he was. I have no idea what his topic was. I DO remember that we were in a hotel meeting room (visual) and I DO remember that he said "Many years ago a computer would fill a room of this size, and now that same computing power can fit in something as small as this little pink packet." And he held up an artificial sugar packet. The room was large; the little pink packet was hard to see. It's a bit of a stretch from computer processing power to sugar packet... but the image (and the point he was making) has remained for decades. That's powerful.

Mental imagery - sometimes it's just impossible to find a photo or physical object to represent your message. Perhaps you are teaching virtually and there is no way to show the physical object (or the object is too big, or too small, or doesn't actually exist yet). Instead you can help learners to create a visual in their "mind's eye." (Definition: To see something in one's visual memory or imagination. Bet you always wondered what that phrase meant. Now you know. The first known use of the term dates back to Chaucer, in 1390. By the time Shakespeare used it in Hamlet, the phrase had been around for over 200 years! )

In Medina's book, Brain Rules (see link above), he talks about DNA and how long and complex it is. He says fitting a strand of DNA in to the nucleus of our cells is like trying to stuff 30 miles of fishing line in to a blueberry. IMPOSSIBLE! But memorable. I may not remember much about DNA in the future, but I will always remember that it is long and complex.

Here is a challenge for you: Go back through the courses you already have and re-evaluate the visuals you are using. Can you add visuals to slides? Can you associate the content with physical objects? Can you make an analogy or tell a story that causes the learner to create a mental image in his "mind's eye?" If you can - I guarantee - recall and comprehension will increase. You will also see test scores go up. Your learners will become brilliant - thanks to you (and visuals).

Updated May 15, 2017: Nelson Dellis, the USA Memory Champ, was recently a guest on Lewis Howes' podcast, discussing how he can easily remember things. One of his tricks is to make abstract things - such as numbers - in to visuals that are easier to remember. For instance, the number 32 is Charlie Brown and the number 95 is Tom Brady. Associating those images with others helps him to combine numbers more easily - so Homer Simpson fighting a sword battle becomes a 4 digit number . This type of visualization technique earned him the record for the longest string of numbers committed to memory - 201. If you have an hour, listen to the podcast and learn about the power of Mind Palaces as a visualization / memorization technique as well.

Teaching Thinking Through Synthesis

According to Bloom's Taxonomy Synthesis refers to the ability to put parts together to form a new whole. This may involve the production of a unique communication (theme or speech), a plan of operations (research proposal), or a set of abstract relations (scheme for classifying information). Learning outcomes in this area stress creative behaviors, with major emphasis on the formulation of new patterns and structures. According to the Merriam Webster dictionary, one definition of synthesis can be:

a combination of thesis and antithesis into a higher stage of truth

What do these definitions mean for us in the training department? How can we teach thinking through synthesis? Here are a few ideas:

In relation to Bloom's definition - ask your learners to read a case study, whitepaper or even an article on a topic and then distill it down to (options:) the most important idea, the most critical sentence, a sentence of their own making, three key words. If you are working with a group of trainees, give each of these assignments to different individuals or small-groups and then compare and contrast their responses. This process requires people to truly think about the content and how to express that content in a way that is easy to remember and agreed upon by all.

In relation to Merriam Webster's definition - have learners read two opposing articles, whitepapers, etc. and then come up with a new, balanced viewpoint or stance. Rarely are ideas completely opposed, so working with the ideas to identify their common ground is very useful in having a well-rounded understanding of a topic.

Writing Learning Objectives

Here is a useful article on Learning Objectives. It will help those who have to write them as well as those who wonder why training takes so long to develop.

The authors use a 5 concentric-circles view with the outer ring being the organizational objectives, and then subsequent circles being roles needed to fulfill the organizational objective, competencies and skills, and knowledge needed by those roles, and finally the learning objective itself.

VERY helpful in understanding how everything is intertwined.

The Limits of Working Memory and Training Effectiveness

In this fascinating blog post from Patti Shank on the ATD site, she discusses the reasons we can't have a one-size-fits-all approach to training.

Aside from the typical learning styles excuse, Patti explores an interesting point related to neuroscience: knowledge and experience dictates the way we can present the content and further impacts the way the learner is able to work with it.

The crux of the difference is working memory vs. long term memory. When newbies are learning a topic, everything they "know" is in working memory - and they are paddling madly to keep processing and applying that information to the learning process. But when a more knowledgeable or more experienced employee has long-term memory associated with a topic, we can work with that topic in deeper and more meaningful ways for the learner.

This chart is an excellent comparison of working memory approaches to training vs. long term memory approaches. This chart may cause you to rethink your training designs altogether.

Is it a Knowledge Check or a Quiz?

In the midst of designing a facilitator-led curriculum for a client, we were met with a conundrum: according to our SME(s), one particular class just had to have a quiz at the end.

There were many problems with this idea, including the fact that none of the other 6 courses in the curriculum ended with a quiz and that the audience was new-hires - so how intimidating would a quiz be?

We finally compromised on a Knowledge Check - that way our SME felt fulfilled (and we fulfilled compliance requirements) but the learners wouldn't be too intimidated (we hoped).

What's the difference?

A quiz is used to check for comprehension. Did your attendees learn what you taught? A quiz can come in many forms - you might ask your learners to recognize an answer, as in the case of a multiple choice text. You might ask them to recall an answer, as in the case of fill-in-the-blank. Or you may ask them to think of the answer by giving a "case" and asking: What should you do next? In all cases the results of the test matter. There is a score (perhaps numeric, perhaps pass/fail). There is a record of that score. And often the scores are compared to one another - resulting in a ranking of some sort.

Alternatively, a knowledge check is more of a review. It's used to determine if the learners can find the answer. They are often allowed to use their learning materials (handouts, workbooks, etc.) and potentially to work together. A knowledge check might be in the form of a game (such as jeopardy) or it might be a solitary activity. Knowledge checks are often used to help solidify the learning, allow learners to review the content one more time, and enable them to leave the training more confident in what they learned.

A knowledge check is appropriate in all situations; a quiz is only appropriate if you have to ensure people know the answers before they leave training. There is some consequence to not knowing the answers (such as performing the job incorrectly), and you need to prove the "results" of the training.

Teaching Thinking Through Comparison

One of the best ways to understand or learn something is to relate the new information to something you already know. Most people don't do this naturally, however. They often struggle with understanding new information and resort to memorization rather than working with the material to really understand it and internalize it.

Since most people don't take the time to do this on their own (or don't know how to), you can assist their learning by designing activities which cause them to focus on this comparison.

One way is to ask them to create an analogy. For instance, How is continuous improvement like a game of golf? Like building a house? Like shopping for a car? Like a basket of fruit?

Another option is to create a story. Assume your learner must learn the inventory layout in a cooking store. Their story might be about a customer who is throwing an important dinner party for their boss. What will they need to make it successful? What would you suggest they buy? Where are those things located in the store?

If you have an on-going curriculum, asking your learners to relate a new topic to the topics they've already learned is a helpful technique. This type of activity not only causes them to have to really understand the new material, but to understand it in a bigger context.

Try any one of these activities in your next training course and see if your learners don't say, "Oh, now I get it!"

Stop Teaching So Much! Learn to Chunk.

We recently reviewed a day-long course on coaching which was actually an excellent class, the only thing it suffered from was the typical: Too much content!

The course taught 4 different coaching techniques and their best-use given a particular type of workplace situation or a particular type of worker, and then participants were given some time to choose one of their own workers with whom they thought the technique might work. Finally, they were divided in to trios to practice the technique.

This learn-and-practice process was repeated four times for each of the four techniques. The problem with this course was that the learning outcomes were just not going to be that great. It is impossible to learn four different techniques, and remember when they apply, and the nuances of usage, when you get back on the job when you've been taught them all in one-fell-swoop.The expected learning outcomes for this class just weren't being achieved, despite excellent content and a "reasonable enough" teaching strategy.

While it certainly takes longer to teach in chunks, and allow participants real-world practice and application, it does lead to better learning outcomes.The next time you are designing a course - especially one that requires practice in order to master - ask yourself: Will people really be able to do Skill #1 when they are back on the job if that information and technique has been "over written" by additional knowledge and skills by the end of the day?

Chances are, you can achieve much better learning outcomes by chunking the content and the periods of teaching, and allowing your participants to have time to not only reflect on what they learned, but also put it in to practice, and then reflecting on how effective that practice and its outcomes really were.

What is most important in solving this problem - Quality, Speed or Cost?

Most of us know the 3-points of any project: quality, speed, and cost, and the fact that it is impossible to have all three.

Given the reality of today's training environment in which budgets are slashed and time allowed for training has been reduced, the question: What is most important in solving this problem, quality speed or cost, is critical to ensure success with any training endeavor.

If quality is most important, then your project will take time and undoubtedly will cost "more" money than a project that doesn't have quality as its most important factor.

If time (project due by the end of this month) is the most important factor, then quality will take a back seat and higher costs will probably prevail in order to get more people or services involved in the creation of the training.

When designing and developing new training for your orginization, this is a very useful question to ask because it helps you to know where to assign your resources and/or it helps you to know what resources to ask for.

So, if time is the most important factor, you may want to request an extra pair of hands such as a consultant or a temporary service. If quality is the most important factor, you may want to price the project and then request an extra 25% in funding.

What is most important to solving this problem: quality, speed or cost is a critical business question which will help you to create a better training product and outcome.

Teaching Thinking through Changing Perspective

One of the ways you can help people to improve their thinking skills is to ask them to change their perspective on a topic. To think about it from another point of view. This is very easy to do in a training situation - since we have folks captive and can ask them to try an activity in a way they are not naturally inclined to.

Unfortunately, we often miss this opportunity in training and instead ask our participants to answer a question based on their own perspective or opinion. For example, how often does your training program ask something along the lines of: Now that you have read the case study, what are the three main factors affecting the situation? Since people respond with their own opinion, we never tell them that they are wrong, of course (nor are they wrong), but do we ever conduct "round 2" of the questioning / debrief and ask the learners, What if you were the banker, contractor, pilot in the situation? THEN what would you say are the three most important factors?

Here are two techniques for getting people to change their perspective on a topic:

1. Collaboration - Having learners work in groups is an easy and natural way to hear more than one perspective. Some care needs to be given to structuring the collaborative activity so that "minority viewpoints" aren't ignored. Perhaps rewarding the group with the most perspectives? Or the most unique perspective?

2. Suggest the other viewpoint - Credit here goes to MindGym and Sebastian Bailey for this simple exercise presented at a conference in 2015. In this type of activity you'll tell the learner exactly the perspective you want them to take. Bailey's exercise went like this: Close your eyes and picture your living room for 30 seconds. Now, picture it again, from the perspective of an interior designer. Again, think of your living room, from this perspective, for 30 seconds. Once more, think of your living room, and this time from the perspective of a robber. What are your insights? What do you see differently? What “Ah-ha” moments have you had? What did you "see" as the interior decorator that you didn't see before? What about from the perspective of the robber?

Interestingly, asking people to change the way they view a situation is something that develops with maturity. It is almost impossible to ask anyone under the age of 18 to change their perspective on a situation. Once someone IS able to look at things from various points of view however, it is wise to continually build that muscle and it will expand their thinking abilities in all areas of their life.

Interview with Connie Malamed: Visual Design Solutions

What motivated you to write this book?

There are many wonderful graphic design books in the world, but none that teach visual design to learning professionals. I see many instructional materials that fail visually simply because most learning professionals are not trained in this area.

A little known secret is that trainers, instructional designers and educators can become competent in visual design by learning the foundation principles of design and applying them through practice. Since I have degrees in art education and instructional design, I wanted to write a book that closes this gap. I wanted to clearly explain the basics of design and demystify what professional designers do and how they solve visual problems.

If you could distill your message down to just one - what would it be?

The message I want to broadcast to all learning professionals is that aesthetically pleasing instructional materials can enhance learning and improve motivation. People make instant judgments as to the credibility and value of a learning experience. Well-designed materials are one critical signal that a learning experience is worthwhile and that the creators care about the learners.

How can training use this book to assist them in the work that they do?

Visual Design Solutions can be read in its entirety as a course in visual design with a learning context. Or it can be used as a reference for design advice and inspiring ideas. The book is divided into four sections and it's easy to start at any point:

The first section will help readers learn to think and work like designers.

The second section explains how to use the three basic elements of design: visuals, text and graphic space.

In the third section, readers will learn how to apply the power principles that will most impact their work (color harmonies, visual hierarchy, unity, etc.)

The final section provides solutions and inspiration to common visual design problems, such as how to transform bullet points into visuals or how to tell a story in visuals.

Do you have a personal motto that you live by (related to the book or your area of expertise)?

The audience is the most important factor in the work we do. When we care about the audience, we will find creative and innovative ways to solve problems and support learning in ways that are well designed and aesthetically pleasing.

Connie Malamed, Learning Strategy Consultant and publisher of The eLearning Coach.

Teaching Thinking Through Debate

Remember the debate club in high school? It was an excellent tool to help young people think critically about various issues and honing their communication skills to be able to intelligently articulate issues. With debate season upon us in the United States, this is an excellent time to point out the thinking skills that are developed through using debate.

Debate requires someone to construct an argument. That argument can be pro or against, but it must incorporate research, analysis, reasoning, and sometimes synthesis and evaluation in order to establish and substantiate one's position. Debate also requires the debater to master their content, to practice both listening and speaking skills in order to counter the opposing side, and to not only be able to verbalize but also to speak persuasively about their position.

These skills are known on Bloom's Taxonomy (here is a quick and easy definition) as higher order thinking skills. Debate takes one beyond the ability to research and "know" information to the ability to construct something and do something with that information.

An additional benefit of using debate in a learning curriculum is that it helps people to understand how to deal with conflict in a constructive and measured way. Countering an opposing argument does not mean name calling, introducing distracting or off-topic issues, or simply blustering louder than one's opponent.

In a previous blog post, we discussed the importance of using questions to help think. In the context of debate however, questioning skills are more musings: What is my position on this topic? What do others say? How do they substantiate their positions? Am I in agreement or disagreement with others? If I am in disagreement with others, how can I substantiate my own position? These types of questions require the skills of research, analysis, synthesis, reasoning, clarifying ... in other words, thinking skills!

Debate as a thinking skill can be used with any topic and in any industry and is best taught in teams (at least 2 individuals) which helps to expand one's thinking as well. Working with one or more teammates requires collaboration skills in order to create a premise, rationale, and presentation.

All in all, debate is one of the best learning strategies you can employ, in order to boost your employee's thinking skills.

Interview with Will Thalheimer, PhD

What motivated you to write this book?

I've worried about my own smile sheets (aka response forms, reaction forms, level 1's) for years! I know they're not completely worthless because I got useful feedback when I was a mediocre leadership trainer-feedback that helped me get better.

But I've also seen the research (two meta-analyses covering over 150 scientific studies) showing that smile sheets are NOT correlated with learning results-that is, smile sheets don't tell us anything about learning! I also saw clients-chief learning officers and other learning executives-completely paralyzed by their organizations' smile-sheet results. They knew their training was largely ineffective, but they couldn't get any impetus for change because the smile-sheet results seemed fine.

So I asked myself, should we throw out our smile sheets or is it possible to improve them? I concluded that organizations would use smile sheets anyway, so we had to try to improve them. I wrote the book after figuring out how smile sheets could be improved.

If you could distill your message down to just one - what would it be?

Smile sheets should (1) draw from the wisdom distilled from the science-of-learning findings, and (2) smile-sheet questions ought to be designed to (2a) support learners in making more precise smile-sheet decisions and (2b) should produce results that are clear and actionable. Too often we use smile sheets to produce a singular score for our courses. "My course is a 4.1!" But these sorts of numerical averages leave everyone wondering what to do.

How can trainers use this book to assist them in the work that they do?

Organizations, and learning-and-development professionals in particular, can use my book to gain wisdom about the limitations of their current evaluation approaches. They can review almost 30 candidate questions to consider utilizing in their own smile sheets. They can learn how to persuade others in using this radical new approach to smile-sheet design. Finally, they can use the book to give them the confidence and impetus to finally make improvements in their smile-sheet designs-improvements that will enable them to create a virtuous cycle of continuous improvement in terms of their learning designs.

Getting valid feedback is the key to any improvement. My book is designed to help organizations get better feedback on their learning results.

Do you have a personal motto that you live by?

Be open to improvement. Look for the best sources of information-look to scientific research in particular to enable practical improvements. Be careful. Don't take the research at face value. Instead, understand it in relation to other research sources and, most importantly, utilize the research from a practical perspective.

Will Thalheimer, PhD, PresidentWork-Learning Research, Inc.

Just In Time Training Has Run Out of Time

Many organizations today are facing a skills shortage. They simply cannot find people with the appropriate skills to run their businesses. As a result, they are forced to hire those that they can and then apply skills-training to make them a worthwhile hire for the organization.

This process can be thought of as a just-in-time skills training program in which the training isn't applied until it is needed (although in 2015 / 2016, skills training is in constant demand).The future-cast for this lack of prepared workers is that in another 10-15 years, the crisis will be a lack of prepared leaders.

In order to prevent businesses (all of society, really!) from bouncing from crisis to crisis like a ball in a pin-ball machine, it's time to address the root cause. It's not that younger generations have suddenly lost entry-level skills - it's a result of never having learned those skills to begin with. You cannot be expected to perform something you never learned to do.

What training professionals can do today to mitigate the current skills deficiency, as well as to thwart the void of leadership in 2025 and beyond, is to rethink the idea of just-in-time training. Rather than applying skills-only-training at the time of need, develop a broader approach to preparing all individuals in the organization by teaching thinking skills.

Is it possible the mortgage meltdown could have been avoided if thoughtful people had contemplated "what could go wrong with giving people 100% financing?" in addition to knowing how to fill out a mortgage application? We think so.

Is it possible that the automobile manufacturers would not have needed a bail out if some thought had been given to the "downside" of leases (massive churning of new cars) rather than simply teaching selling skills? We think so.

It's relatively easy to overlay thinking skills on top of job-specific training. For instance, when teaching how to prepare financial reports, a discussion can be had around the topics of ethics and erroneous reporting (intentional or not), and the ramifications to the organization of inaccurate financial reports (underestimating income, miscalculating forecast, personnel balancing). When teaching business writing, there might be a research project associated with the implications of having a paper-trail or the importance of choosing words that are unambiguous.

It is important to teach not only "how to," but "what if." Asking learners to think deeper and wider about the skills they are learning will help them to contribute more to the organization now and in the future.

Visuals Enhance Learning

"Pictures are understood on many levels. The most literal level is what the picture depicts. When you see a line drawing of an airplane, you recognize the shape and features of the object and identify it as an airplane.

“On another level, the context of the picture provides meaning. The same picture of an airplane on a freeway sign means that an upcoming exit will take you to the airport. This is a different context than a photograph of an airplane you may see in an airline advertisement, which suggests that is is persuasive rather than an informational purpose.

“Understanding the meaning of the picture depends on the context of where the picture exists. Another level of meaning is based on the style of the graphic. This is expressed in many ways, such as through symbols, spatial layout, and accepted conventions. For example, certain attributes of an illustration indicate when a drawing is an architectural blueprint and when it is a scientific illustration.

“There are also metaphoric meanings in some graphic. Metaphors convey meaning beyond a simple depiction and provide another layer of meaning."

Excerpted from Connie Malamed's Visual Design Solutions - a fantastic text for understanding the power of using visuals in learning.

Could they do *it* in the past?

Here are two questions that should be asked during a needs assessments to help ensure that you are not designing and developing training unnecessarily, and also to ensure that the training you ARE creating is appropriate for the "gap" that needs to be augmented.

Question #1: Have the learners been able to do ____ in the past?

Question #2: Have the learners had training on ____ in the past?

Let's look at why each of these questions is important to ask.

Have they been able to do ________ in the past?

Typically, if an individual or group has been able to successfully complete a task in the past, and suddenly are not able to, it is not because they forgot how to do it. It's more likely that conditions within the work environment have changed. Look at factors such as:

Have new metrics been put in to place? (causing people to do their work in a less thorough manner?)

Has a new process been added which conflicts with the standard operating procedure?

Are people incentivized to do the job differently / poorly?

For instance: In a call center environment, CSRs can be incentivized to solve a consumer's problem on the first call or they can be incentivized to complete as many calls per hours as possible. Typically, those are two competing end goals. So, if you have workers who have been able to do a process or task in the past, and suddenly they are not - the last thing you should assume is that the fault lies with the workers.

Have they had training on this topic in the past?

If the answer to this is "yes," then the next question is: Why didn't that training stick? Or... did the company forget they had a training program already in place?

Any new skill will fritter away if it is not used. Often people go through training but then get back on the job and have to catch up on a backlog of work. In order to catch up quickly, they will resort to their "old way" of doing things. This aligns with the bullet points above - are trainees incentivized to "keep up the pace," or to do things in the "new and improved" way? If the latter, they will need time to practice and become proficient.

In other instances the newly trained individual simply isn't given the opportunity to put in to practice what they have learned. Example: One of our clients put learners through a 12-week, job-specific training program but then assigned them to a starter-job for 6 months before they were allowed to do the job they were just trained to do. It was "efficient" for the company to give people the 12-weeks of training right after they were newly hired, rather than take them off the job later on. But the newly trained individuals weren't allowed to actually put their skills in to practice until they had "paid their dues" by being on the job for 6 months or more.

It's tempting to jump right in and solve the problem - but first step back and ask "why does this problem exist?"

*Credit to Bob Mager for the basis of these questions.